Zeng Nanjin, Huang Yebin, Li Shuqi, Liu Yixin, Zhang Yichen

programme:Master of Economics (quantitative economics) in National University of Singapore

Our research group members review the paper, The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns, which set up the foundation for this famous model. Our work includes 3 sections. Section 1 summarizes this paper. Section 2 demonstrates the Fama-MacBeth regression shown in the paper, with data in China’s stock market. Section 3 is our comment.

1.Summary

The main idea of this paper is to verify that β in the SLB model cannot effectively explain the fluctuation of return and to show that size and book-to-market equity are two very significant factors to explain the average return. First of all, many studies have shown that market β in SLB model cannot explain expected returns, and other factors can be used to explain the fluctuation of returns, such as size, BE/ME, E/P, leverage, etc. Next, the authors study the relationship between size and β. The stocks in NYSE\ AMEX \NASDAQ, excluding highly leveraged financial companies, are divided into ten groups depending on the size. Each group is then subdivided into ten portfolios according to pre-ranking β of individual stocks. The authors calculate the weighted average return of each portfolio every month as the post-ranking monthly rate of return to obtain post-ranking β. Then they reach the following conclusion: when the combination of stocks is only based on size, both of size and β have significant correlation with average return, but there is also a correlation between β and size. However, if the size is controlled, the relation between average return and β will disappear which implies there may be a spurious correlation between them. After that, the authors use cross-sectional regression to show that β is not significant in explaining the average return. The authors continue to find the relation between average return and BE/ME, E/P, leverage separately. It comes to the conclusion that BE/ME has a significant positive effect on average return and has more explanatory power than size. Moreover, he finds that BE/ME can absorb the effects of leverage and E/P ratio on average return. At last, the authors add a note: although these tests assume a rational asset-pricing framework, BE/ME can also predict the return of stock after the overreaction under irrational asset-pricing condition is corrected.

2.empirical data application

2.1 Data and model setting

We collect data of all 180 individual stocks of SSE CONSTITUENT INDEX from Wind Database and by removing financial firms and firms without completed data, we finally use 104 stocks to be our sample. We set the sample period from May, 2013 to April, 2020, including 72 months. The reason why the sample period begins from May in year t is that the Securities law of China (Article 79) requires listed company submit annual financial report within 4 months as of the end of each accounting year (that is to say, no later than April 30th). Two steps we take are shown as following:

Step 1: 104 individual stocks are divided into 24 portfolios according to size and pre-ranking \(\beta_{i}\). Then post-ranking \(\beta_{p}\) is obtained using portfolios and is assigned to each stock in this portfolio. This portfolio formation processing is repeated in May of every year t from May, 2015 to May, 2019 and both of pre-ranking \(\beta_{i}\) and post-ranking \(\beta_{p}\) are calculated using Time series regression as the paper did.

Step 2: In the cross-sectional linear regression, in every year t from May, 2015 to April, 2020 (including 60 months), we use firms’ financial data (ME, BE, Asset, E/P) of the end of year t-1 and post-ranking \(\beta_{i}\) obtained in the first step to test their explanatory power for returns. Coefficients of these variables are reported as averages of slopes of every month regression.

2.2 Empirical Result

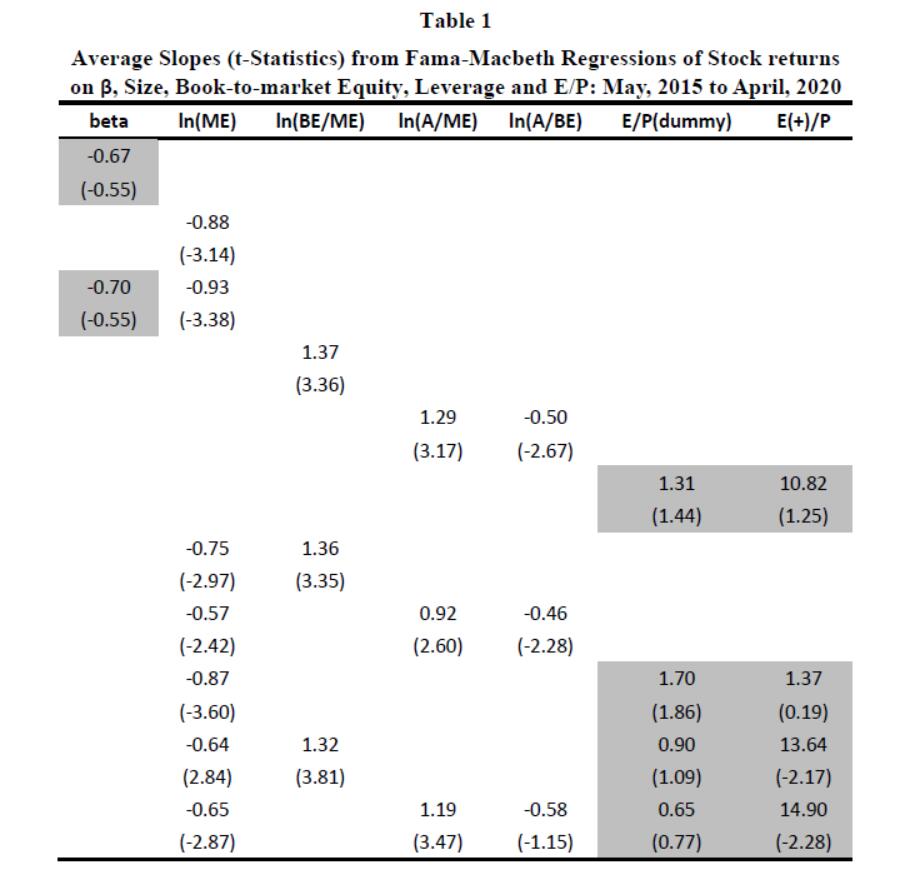

We have 11 regression models. We show the average value of the regression coefficient in each row and give the T-statistic in parentheses. In multi-regression, there are several values in a row, which means that the regression analysis is performed on these factors simultaneously.

As shown in the table 1, our conclusion is consistent with the original paper.

(1) In the single-factor regression, there is a strong negative correlation between the size and monthly return, while β has no significant impact on return. Meanwhile, there is also a high correlation between book-to-market equity and returns. Moreover, book-to-market equity has a greater influence than size.

(2) A two-factor regression model based on size and book-to-market equity can be used to estimate the expected average return.

3.Comment

Above all, as we discussed in section 1, this paper is a settlement for a series of papers about the empirical study in the application and validity of Sharpe-Linter-Black model. The result of this paper uses Fama-Mecbeth regression to verify that, β cannot effectively explain the fluctuation of return rate and give two effective alternative factors, size and book-to-market equity. These factors have strong explanatory power even in other stock market around the world. By now, the Fama-French Three-Factor model, which is derived from this paper, is still used in industry and by scholars. It shows that the result of this paper has strong external validity, and it is a sign for the large contribution of this paper to Finance. From the view of our group members, this paper has many sparkling points which worth studying. However, we consider that the paper could be further improved. This paper is a pure empirical study for the efficiency of factors in explaining the return of stock. A possible problem for this paper is that, it lacks of mathematical proof for the reason why size and book-to-market equity would be two dominating factors explaining the monthly return of stock. In this paper, the authors process their model selection because,

- Existing study cannot give an explicit conclusion about which alterative factors should be used.

- Most of these factors are scaled versions of price. It leads to a natural thought that some of them are redundant. Though we notice the authors have some other paragraphs discussing the reason why size and book-to-market equity work well, neither of these discussions have rigorous mathematical proof. In that case, the reader would concern the external validity of the result, since without a reliable identification logic, the statistical result may come from occasion and work poorly for another dataset. Though the external validity of this paper has been proven by lots of paper testing its validity in following years and different stock markets, that would be a problem if we perform our own empirical study.

Moreover, our group members want to give some notice in application of this model. We should make some proper local adaptions before we use this Fama-French Three-Factor model and run the Fama-Mecbeth regression. For example, in another paper performs Fama-French method in China’s stock market, Liu et al. (2018) finds that since the smallest company have “shell value” in potential reverse mergers under tight IPO policy, excluding them from data would increase the explanatory power of the model. Compare to this case, if we filter the data with proper rules to capture the local characteristics, concerning the policy or market condition, we may further improve the validity of Fama-French model. That is why we change the explanatory period from “July, t year – June, t+1 year” to “May, t year – April, t+1 year” when we perform the model in China’s stock market in section 2. It could make sure that we use the latest available accounting data for every data point in regression, to act like a true investor at that time.

Bibliography

Fama, Eugene F., and James D. MacBeth. (1973). Risk, Return, and Equilibrium: Empirical Tests. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3): 607-636.

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. (1992). The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. The Journal of Finance, 47(2): 427-465.

Liu, Jianan, Robert F. Stambaugh and Yu Yuan. (2018). Size and value in China. Journal of Financial Economics, 134(1): 48-69.